Back in 2011, my local paper asked me to review a Daughtry show. This experience shook me. The massively popular American Idol-approved band represented the worst nightmare of a listener who once worshipped the likes of Pearl Jam and Alice In Chains – not “post-grunge,” but “post-post-grunge.” Daughtry ripped off Eddie Vedder, but by way of Scott Stapp. It was like a mad scientist created club-footed, brain-dead clones of the best bands of the 1990s, and then made those clones procreate. This concert filled me with pop culture paranoia – was any of the music I grew up with actually any good?

Which is a long way of explaining why I decided to revisit the soundtrack to my high school and college years, and list my top 100 albums of the decade. It was refreshing to realize that, even seen in hindsight’s harsh, unforgiving light, a lot of the stuff I loved holds up. I’m sure nostalgia is clouding my judgment on many of these choices, but jeepers creepers, I’m only human.

So, when the biggest rock band of 2021 credits Daughtry as its main influence, I’ll have this list to come back to, and remind myself that yes, it’s still good.

100. Moxy Früvous – Bargainville (1993)

100. Moxy Früvous – Bargainville (1993)

Remember how I said that thing about nostalgia just now? Well, this record’s on here largely because of it. Don’t get me wrong, Moxy Früvous was teeming with talent – a Toronto quartet of multi-instrumentalists who harmonized like a hybrid of The Beatles and The Andrews Sisters. But in concert was where the group really shone; its energy, humor, and awe-inspiring tightness made for some of the most memorable live experiences of my teenage years. Bargainville is its best album, a mix of poignant folk and quirky novelty tunes. Listening to it today does make me cringe just a bit – why, oh why, does it begin with a ballad about our dying environment (“River Valley”)? Sure, Bargainville might be an awkward mix of the self-serious and the seriously nerdy. But that’s also a dead-on description of me at 15.

99. Dr. Dre – The Chronic (1992)

99. Dr. Dre – The Chronic (1992)

If this exercise was an attempt at listing the albums I loved and obsessed over in the 1990s, The Chronic would crack the top ten for sure. I was 10 when Straight Outta Compton came out, so Dr. Dre’s solo debut was my first exposure to the lurid, hilarious and irresistible world of gangsta rap. But listening to it now is a bit of a chore – the production remains some of the best in rap history, and Snoop Doggy Dogg’s flow is unimpeachable, but so much of the lyrics are bogged down by Dre’s obsession with his own personal beefs, and frankly, his mediocre rapping ability. To quote Chris Rock: “It’s hard to drive around singing songs about ‘Easy-E can eat a big fat dick.'” Also, this might be the most misogynistic hit record of all time. The song “Bitches Ain’t Shit” is ironic, because the song is most definitely shit. Hearing this album now makes me understand why I can’t get with artists like Odd Future, despite a sound that appeals to my sensibilities – it’s a pain in the ass to have to constantly rationalize to myself why I like something. Despite all of this, I still can’t deny a genius when I hear him; The Chronic makes this list because of Dre’s production wizardry, a singular talent that would shine even brighter on the superior Doggystyle.

98. Lauryn Hill – The Miseducation Of Lauryn Hill (1998)

98. Lauryn Hill – The Miseducation Of Lauryn Hill (1998)

I don’t want to be one of those people who calls something like Lauryn Hill only releasing one album “tragic.” But it is a bummer. Especially when you consider the major flaw of her magnificent debut – its 77-minute running time. So much of The Miseducation of Lauryn Hill is so impressive, blurring the lines between R&B, gospel and hip hop, laying down a “neo-soul” template that few would come close to matching, brilliantly juxtaposing the bitterness of failed love with the hopes and mysteries of childbirth. Still, it’s tougher than it should be to get through the whole thing, what with the schoolroom skits, the hidden Frankie Valli cover, and the stretch of five long R&B tunes that get you from “Final Hour” to “Everything Is Everything.” One hoped that Hill’s future efforts would maintain this dizzying level of artistry, while exhibiting a stronger ability to self-edit. But that was a lot to expect, it turns out. This one’s all we have, and we should thank god for all 77 of those minutes.

By the time ska-punk and swing had infiltrated the mainstream in the mid-’90s, I was immersed in it. Looking back, it’s embarrassing to remember Carson Daly introducing a Reel Big Fish video in a two-tone suit, and it’s more embarrassing to remember how much I loved Reel Big Fish. But even after all this time, and all the guilt I’ve had to process, there’s no doubt in my mind – Sublime’s third album kicks ass. And I don’t care how many frat boys in pre-torn South Carolina Gamecocks hats agree with me. Bradley Nowell’s swan song revealed him as some kind of stoner-poseur genius. He appropriated hip-hop and reggae tropes in ways that should’ve been embarrassing. He sang about tits, butts and bong loads. But his voice ached and cracked with seemingly unwarranted pathos. Were we hearing an addict struggling to hold on to the good times? Were we just hearing a super-talented guy at his peak? No matter the reason, Sublime rules, bro.

96. Soundgarden – Superunknown (1994)

96. Soundgarden – Superunknown (1994)

Grunge is often credited as the genre that snuffed out hair metal, which is suspect at the very least. But it’s ironic that Soundgarden was one of these vaunted acts allegedly responsible for killing the Crüe, poisoning Poison, and slaughtering Slaughter (I’ll stop there). While it did a better job with the follow through, the band’s formula wasn’t so different from Whitesnake’s – Zeppelin-esque ambition, Sabbathy riffage and a disarmingly pretty lead singer. If you had to bet on one of those Seattle bands becoming rock stars, they were the obvious choice. And Superunknown made good on all of this critical and commercial potential, a darkly tinged arena rock album with just the right mix of killer riffs, power ballads and moody meditations. Its only misstep is “Kickstand,” an workmanlike attempt at snarling punk that just underlines how different Soundgarden was from Nirvana. But what it lacks in gut-punching attitude, Superunknown makes up for in production value. An immaculately crafted work, performed by a singer and lead guitarist at the pinnacle of their powers, this is Soundgarden realizing its destiny – to play those big-ass venues that David Coverdale and company used to pack to the gills.

95. Primus – Sailing The Seas Of Cheese (1991)

95. Primus – Sailing The Seas Of Cheese (1991)

“As I stand in the shower/Singing opera and such/Pondering the possibility that I pull the pud too much/There’s a scent that fills the air/Is it flatus?/Just a touch/And it makes me think of you.” This, my friends, is the essence of Primus, a band that thrived on bass solos, dissonance, nasal sing-speak and songs like “Grandad’s Little Ditty,” the old-weirdo-in-the-shower vignette that my friends and I would croon to each other like it was a Perry Como ballad. It’s just one of many moments on Sailing the Seas of Cheese made to be obsessed over by strange teenage boys, on an album that should’ve aged terribly on paper. But Les Claypool, Larry LaLonde and Herb Alexander happened to be very gifted musicians, and the obtuse nerd-funk grooves they let fly on “Jerry Was A Race Car Driver,” “Is It Luck?” and “Tommy The Cat” are evergreen. The band eventually lost me with 1995’s Tales From A Punchbowl, but for the record, it wasn’t because I’d become an adult or anything – to this day, “Grandad’s Little Ditty” makes me laugh.

94. Tom Waits – Mule Variations (1999)

94. Tom Waits – Mule Variations (1999)

After releasing the harrowing Bone Machine in 1992, Tom Waits took a break (1994’s The Black Rider was the soundtrack to a play he wrote and began recording in 1989). When he returned seven years later, it was to introduce yet another phase of his illustrious career. Not a Swordfishtrombones-level reinvention, mind you, but a nuanced move similar to the one Bob Dylan was making at the time – an organic, nostalgic embrace of Americana. The blues always informed Waits’ sound, whether through the hotel bar piano playing of his early records or the wonky pentatonics of his ’80s avant garde period. But on Mule Variations, the style comes through with a clarity that no Waits album, before or since, has possessed. “Lowside of the Road,” “Get Behind the Mule” and “Filipino Box Spring Hog” could all be Muddy Waters covers, and ballads like “Picture In A Frame” take the 12-bar structure into achingly beautiful places. Waits also dabbles in gospel, spoken word and adult contemporary (still waiting for Rod Stewart’s cover of “Hold On”), all with the same clear-headed approach. He lets the songs do the heavy lifting here, minimizing his vocal flights of fancy and keeping the clanging percussion to a minimum. Now I happen to really like those two things, which makes Mule Variations a second-tier Waits album in my mind. One that still kicked the shit out of most of the albums released in the ’90s.

93. Ice Cube – AmeriKKKa’s Most Wanted (1990)

93. Ice Cube – AmeriKKKa’s Most Wanted (1990)

At NWA’s height, its most talented rapper broke away and went right coast, making a solo album with The Bomb Squad, the production team responsible for Public Enemy’s massive, martial sound. I was too young to know about all of this, but for rap fans at the time, it must’ve been like John Lennon joining The Rolling Stones. To top it off, AmeriKKKa’s Most Wanted delivers. Ice Cube is at his most breathtakingly volatile, charging out the gate yelling, “I’m sick of getting treated like another damn stepchild!” A simultaneous description of his falling out with NWA and the common plight of African-Americans, the song, “The N***a Ya Love To Hate,” proved Cube was up to the challenge posed by the Bomb Squad’s crackling soul thunder. Like every gangsta record from this period, Cube’s verses devolve into meathead misogyny from time to time. But the prevailing mood is righteous anger, with the ultimate goal of shining big, fat flood lights on life in Los Angeles ghettos, exposing the problem underlined by the Tom Brokaw clip that kicks of “Rollin’ Wit The Lench Mob”: “Few cared about the violence, because it didn’t affect them.”

92. Everything But The Girl – Temperamental (1999)

92. Everything But The Girl – Temperamental (1999)

I was never more than a casual fan of electronica during its ’90s heyday, appreciating its propulsive energy and imaginative approach to sampling, but always returning to rock and hip-hop at the end of the day. But a few of these records managed to break through my stubborn listening routine, including this one, in which Everything But The Girl suggested a world of listening possibilities that I was willfully ignoring. Temperamental wasn’t like any electronica I’d heard, a mix of moody synthesizers, jazzy samples and laid-back drum loops that wasn’t meant to get anywhere close to the dance floor. Tracey Thorn’s voice floated majestically over these post-punk techno pastiches, analyzing fizzled relationships with a resigned sense of grace. It’s a beautiful soundtrack for a long bout of after-hours introspection, and while this approach was nothing new to EBTG fans (Temperamental was its 10th album), it was, and remains, an eye-opener for me.

91. Cracker – Kerosene Hat (1993)

91. Cracker – Kerosene Hat (1993)

Cracker doesn’t get the breathless critical raves of its contemporaries, despite Kerosene Hat being in the same alt-country ether as Uncle Tupelo’s best work. That probably has everything to do with “Low,” the huge-ass hit song that was the only way a kid like me could become aware of David Lowery’s post-Camper Van Beethoven ensemble. Despite its rootsy, Tom Petty & The Heartbreakers groove, “Low” bumped shoulders with “Heart-Shaped Box” and “Today” on radio playlists, meaning Cracker was seemingly all about the “alt,” and not about the “country.” Which just ain’t the case. Dusting off this disc has been the most pleasurable thing about this whole project so far; I’d simply forgotten how great these songs are – “Get Off This” and “Sick Of Goodbyes” join “Low” as examples of alt-country at its peak.

90. Cibo Matto – Stereo ★ Type A (1999)

90. Cibo Matto – Stereo ★ Type A (1999)

As delightfully trippy as it was, Viva! La Woman, the first album from the duo of Miho Hatori and Yuka Honda, boasted a formula that seemed best suited to a one-off project – a band that names itself after the Italian translation for “crazy food,” and writes a bunch of weird acid-jazz songs about food. But luckily for us, instead of belaboring things, Cibo Matto expanded its artistic vision, along with its lineup, for its outstanding follow-up. Gastronomy is only a passing fancy here, with Hatori and Honda applying their distinctly strange lyrical touches to wider themes of love and cosmology. More importantly, they keep the non sequiturs to the verbal realm – Stereo ★ Type A ditches the muddier patchwork production of Viva! for widescreen accessibility. On the earwormy dance-pop of “Spoon” and “Lint Of Love,” the geek-rap of “Sci-Fi Wasabi,” and the light samba of “Stone,” Cibo Matto suddenly sounded like a group that was meant to make great records deep into the next millennium. Of course, they broke up in 2001.

89. Barenaked Ladies – Maybe You Should Drive (1994)

89. Barenaked Ladies – Maybe You Should Drive (1994)

Here’s the second wonderfully talented Toronto band to appear on this list, and hindsight hasn’t been kind to either. But unlike Moxy Früvous, who was just more of a live animal, Barenaked Ladies’ oeuvre is colored by the mainstream success it experienced later in the decade – success that can mostly be attributed to one completely obnoxious single, and a handful of innocuously bland tracks released in its wake. Listening to the band’s earlier work now, I can’t help but look for evidence of the “One Week” formula everywhere (finding it all over its debut, Gordon, for the record). But Maybe You Should Drive emerges from this pop forensics investigation largely unscathed. It’s the band’s most “grown-up” album, a collection of cleverly penned, XTC-indebted pop tunes and whisper-serious ballads. Steven Page was on a roll here, contributing his classic unrequited love song “Jane,” the country-pop beauty “You Will Be Waiting,” and the charmingly unabashed novelty cut “A.” And while Ed Robertson’s groovy folk melodrama “Am I The Only One?” might not clench my heart the same way it did 18 years ago, it still has its way with me when it comes on. I selfishly wish BNL stayed down this path, instead of beginning their inexorable decline with the forced cheerfulness of Born On A Pirate Ship. They most certainly wouldn’t have hit pay dirt in that fashion, which is why I don’t manage rock bands for a living.

88. Arsonists – As The World Burns (1999)

88. Arsonists – As The World Burns (1999)

As The World Burns begins with a clever nod to “A Day In The Life,” blending studio chatter with a clip of that string section burning chromatically through the octaves. The reference works, because while As The World Burns isn’t Sgt. Pepper’s, both albums share a similar goal – to off-set the expected with the occasional tripped-out detour. Arsonists gives you the adrenalized street-rap showcases you’d expect from a late-’90s Brooklyn hip-hop group, like “Backdraft” and “Shit Ain’t Sweet.” But they follow them up with “Pyromaniax,” a track that finds MCs Q-Unique and D-Stroy getting profoundly whacked over a goofy calliope loop, to the point where they’re doing a Monty Python-esque impersonation of a screaming Cockney couple (an experience that rivals dog whistles and backwards recordings in the fantastically strange department). It reminds me of a recent Wu-Tang show, where Method Man spent a good amount of time complaining about how today’s hip-hop artists have forgotten how to have fun. I’m not sure I agree with him, but listening to this album does make me see his point – we don’t hear too many records like As The World Burns these days, albums whose only goals are to stop people in their tracks, get them laughing, and keep them dancing.

87. Tori Amos – Boys For Pele (1996)

87. Tori Amos – Boys For Pele (1996)

As a teenage boy who spent the ’90s attempting to play keyboards and pretending to not be deathly afraid of girls, I was heavy into Tori Amos. Sure, I didn’t understand much of anything she was singing about, but it was art, man. Sensitive art that showed what an amazingly sensitive man I was. As I slowly grew out of this cocoon, met my ravishing wife, and realized that few things were more insufferable than a man who hopes his CD collection will get women to like him, Amos’ records lost a bit of their magic to me. With the exception of Boys For Pele, that is. Here is everything this artist does best – shimmering waterfalls of piano and harpsichord, dramatic dynamic shifts, the occasional stone-cold groove, and lyrics that go where the flakiest lyricists fear to tread. Like any Amos album, it’s indebted to Kate Bush, but Pele has her discography’s highest percentage of original ideas, from the neo-classical piano licks of “Father Lucifer” to the grinding harpsichord riffage of “Professional Widow” and the rainy day blues of “Little Amsterdam.” And as a player, Amos is brilliant, communicating to us through her instrument, often by just letting the chords do their thing.

86. The Mighty Mighty Bosstones – Question The Answers (1994)

86. The Mighty Mighty Bosstones – Question The Answers (1994)

I mentioned this in my comments about Sublime earlier, but you probably didn’t read that, so I’ll say it again – I was once smitten with the mid-’90s mini-revival of ska/punk. As a quiet kid with plenty of pent-up energy, I loved these bands with seemingly boundless reserves of adrenaline, soaking up their irreverent material and catchy horn parts. But like anything that’s heavily templated, 95% of this stuff was too repetitive to make any lasting impact on my listening habits. The Mighty Mighty Bosstones are one of the few artists that survived this ska-pocalypse; they were a party band, yes, but one with a little depth and nuance beneath all the fun hooks. In my view, they were able to do what no other group could – staying comfortably within the restrictive ska-punk guidelines (horn section part, sped-up reggae verse, thrashy punk chorus, repeat) while crafting a sound that’s completely their own. Question The Answers was the zenith of the group’s rowdy-yet-accessible sound, combining “singer” Dicky Barrett’s Tom Waits-meets-Henry Rollins growl with some of the decade’s most skillfully arranged horn charts (the riff on “Hell Of A Hat” is that forever kind of cool). Jet-fueled punk tunes like “Dollar And A Dream” and “365 Days” contrast nicely with the poppy nostalgia of “Pictures to Prove It.” And the working-stiff lament “Jump Through the Hoops” closes everything with an effective mix of the boisterous and the forlorn. Put it all together, and you’ve got a record with wider shades of grey than any ska-punk band had a right to explore.

85. Eminem – The Slim Shady LP (1999)

85. Eminem – The Slim Shady LP (1999)

Remember when Eminem was funny? Before he was equal parts hero and pariah? Before he cared about haters and leaned on melodramatic drug metaphors? It’s understandable if you don’t, because the polarizing MC only had one album under his belt before he became a passionately beloved and despised superstar. The Slim Shady LP will always be his best musical accomplishment, because it couldn’t possibly be tainted by the rapper feeling like he had to respond or live up to anything. He could be a scrawny no-name white dude hilariously berating Dr. Dre for condoning non-violence, the moment that, for me, best encapsulates the joy of Eminem’s debut. The song, “Guilty Conscience,” was a brilliant concept – have Em play the devil, and Dre play the angel, appearing over the shoulders of a series of protagonists experiencing moral crises. By pitting this mega-talented youngster against his legendary old-guard producer, challenging him to be relevant again, reminding him how much fucking fun music could be, the track bristled with a thrilling kind of energy. Not to say Marshall Mathers couldn’t carry a tune on his own; the rest of the record finds him unfurling verses full of snarky humor and random blasts of open-vein honesty, over dance-floor ready beats that remind us these tracks were not meant to be taken too seriously. The most controversial cut is also one of the best – a blistering spoof of Will Smith’s squeaky clean “Just the Two of Us.” “’97 Bonnie and Clyde” puts the rapper in the shoes of a father driving his baby down to the beach, so he can dump his wife’s body in the ocean. Like a South Park episode that creates an entire plot line just so it can make fun of a celebrity, Eminem crafted this pitch-black satire for the express purpose of dissing Smith’s bland, pandering hit. Future albums would have snatches of this vibrant, rebellious personality, but ultimately fail, because Eminem had become one of those people he so gleefully skewered on The Slim Shady LP – somebody who gives a fuck.

84. Urge Overkill – Saturation (1993)

84. Urge Overkill – Saturation (1993)

After grunge and alternative rock exploded, A&R execs bent over backwards to sign any band with loud guitars and self-loathing issues. Criticize the approach if you will, but it did result in a major label contract for Urge Overkill, despite the fact that the band wasn’t all that grungey, sounding more like Elvis Costello moonlighting in a cock rock band (not exactly a template to get them on “120 Minutes”). Yes, Saturation, the group’s first effort for Geffen, shares some of the same glam influences as fellow Chicagoans Smashing Pumpkins, and a couple of the riffs possess a slight whiff of Seattle grit. But the pervading mood is Saturday night swagger, not Sunday morning regret. Whether they’re tearing through big, shiny rock anthems like “Sister Havana,” filthing things up with the bloozy riffage of “The Stalker,” or channeling the Ramones on the kinetic “Woman 2 Woman,” Urge Overkill put their desires to be bad-ass above any need to make deep emotional connections (the exception to the rule being the stunning ballad “Dropout”). Add singer Nash Kato’s rich, puckish tenor to the mix, and you’ve got one of the sexiest LPs to ever be pigeonholed as alternative rock. Urge Overkill might’ve worn flannel, but it was most definitely obscured by black leather jackets.

83. Outkast – ATLiens (1996)

83. Outkast – ATLiens (1996)

“Holding on to memories like roller coaster handle bars,” shares Andre 3000 on “E.T.,” one of the many subdued, introspective tracks on ATLiens. It’s an apt sentiment on a record that finds the motormouthed twosome exploring sounds that had little to do with the past, ending up with a record that could arguably be called the birthplace of Dirty South hip hop. Casting themselves as Peach State aliens with checkered pasts, uncertain futures and healthy egos, Andre and Big Boi were fully aware of the bold artistic leaps they were taking on their second album. Leaving the Death Row-Native Tongues hybrid of its debut in the dust, Outkast isn’t afraid to let the music simmer to a slow boil, building “Wheelz Of Steel” on little more than a mournful B3 loop, crafting something truly ominous with the soft vocal hums of “Babylon.” Equally important is the duo’s remarkably constrained vocals; both rappers manage to temper the volume of their rapid-fire verses, without sacrificing any of their intensity. ATLiens suffers a bit from the even more rarified air explored on ensuing Outkast albums, where its formula was expanded to include Parliament-sized funk workouts and world-beating pop singles. These days, it plays like the artful come-down after Stankonia’s life-changing mind fuck. Which is surely cooler than a polar bear’s toenails.

82. Emmylou Harris – Wrecking Ball (1995)

He’ll probably be best remembered for the massive hit records he produced in the ’80s, but it’s the deeply resonant career resurrections of the ’90s that impress me most about Daniel Lanois. The producer proved himself to be the polished, perfectionist counterpart to Rick Rubin, exhibiting an uncanny ability to put his own, richly detailed touches on albums by artists with their own fully developed egos (a decade working with Bono will do that). On Emmylou Harris’ 17th album, Lanois pulls off the most sophisticated trick of his career, de-twanging the arrangements for the legendary country songbird, relying on her inimitable voice as the only connective tissue between her previous work and this lushly produced blend of adult contemporary and Americana. It was a calculated risk, one that paid off beautifully. Wrecking Ball is a gorgeous offering of wide-screened, cloudy sky pop, on which Harris proves Lanois right with every syllable she sings. Her crystalline instrument infuses all the regret and hard-earned joy these tracks call for, bringing songs by Neil Young, Steve Earle, Gillian Welch, Jimi Hendrix and Bob Dylan to new levels of delicacy and poignancy, supported all the way by Lanois’ generous washes of reverb. It’s the kind of record that could start a spirited “what is country?” debate – is it the instrumentation and the subject matter, or is it a more intangible vibe? If you’re prepared to argue the latter, make Wrecking Ball your Exhibit A.

81. The Black Crowes – Amorica (1994)

81. The Black Crowes – Amorica (1994)

For somebody following a band from the very beginning, there’s no better moment than the realization that they’ve elevated their game. To somebody who would have been thoroughly pleased with the same old, same old, even the smallest sign of growth can hit like a firecracker. Yeah, I know I’m talking about The Black Crowes, whose brand of Georgia bellbottom boogie isn’t normally associated with artistic boldness. The band initially caught on as fodder for fans of classic rock dinosaurs in the early-’90s – a time when my love of classic rock dinosaurs was at its peak. I got heavy into the Crowes, loving how Chris Robinson sang to the rafters over all the southern-fried Zeppelin riffs and gospel slow-burns. By the time Amorica came out, the group’s first two albums were classics in my mind. So when I first heard how loose and confident they sounded on the percussion-heavy groove of “Gone,” it was like a Stones fan hearing Beggars Banquet for the first time. That familiar sound had become something richer, earthier, and more significant. Now that it’s been almost 20 years since Amorica gave me that feeling, its pleasures have descended from the spiritual plane. But pleasures they remain, from the organic grooves of “High Head Blues” and “Wiser Time” to the regret-laden epic “Cursed Diamond” and the gorgeous, stoner/Bruce Hornsby ballad “Descending,” whose piano outro still chokes me up.

80. Propellerheads – Decksanddrumsandrockandroll (1998)

Whether they’re the result of the legitimate, organic rise of a new artistic sensibility, or something manufactured by critics who are magnanimous with their “next big thing” proclamations, all pop music trends are fads, destined to flame out. So instead of letting them dictate the way you walk, talk and dress, why not do something that will never go out of style – find a good groove and dance to it. This is the message of Propellerheads’ single “History Repeating,” a propulsive spy movie rave up, complete with a gutsy Shirley Bassey vocal, that realized the mainstream potential of electronica while mocking the hype machine that had been predicting just that for years. On the British duo’s first and only LP, they give several examples of the kind of tracks that could inspire critics to go all Nostradamus, doing monstrous things with drums and bass lines that could seemingly stretch on forever without losing their adrenaline-spiking energy. “Take California,” “Bang On!” or the Matrix-approved “Spybreak!” make driving to work feel like a million-dollar chase sequence. When sequenced with quieter, quirkier moments like the groovy kitsch of “Velvet Pants” and the loping, skater hip hop of “360 (Oh Yeah?)” (which features De La Soul at their effortless-sounding best), Decksanddrumsandrockandroll becomes an evergreen listen, an album that will always be as much fun as it was the day it came out. My flannel is long gone, and these beats are forever.

79. RZA – Bobby Digital In Stereo (1998)

79. RZA – Bobby Digital In Stereo (1998)

By the time RZA got around to releasing an album under his own name, he was seen as a pretty solid hip hop double threat – a genius producer who had garnered respect as a rapper as well. Bobby Digital In Stereo solidified this status. Not only was it the treasure trove of dramatic, confrontational beats we’d come to expect (and this a year after the double-LP Wu-Tang Forever. Damn, were we spoiled), it was the first real revelation of RZA’s abilities on the mic. He dishes out some wild, brilliant tongue-lashings here, making the record’s kinda lame “digital v. analog” concept sound like the toughest street battle this side of Mobb Deep, and shouldering the burden of keeping the adrenaline flowing over the course of 17 tracks. That said, Bobby Digital drags just a bit in the middle, but it’s thanks to a glut of guest rappers (RZA only contributes six verses from tracks 8-15). And it pretty much doesn’t matter, because the man closes things in unforgettably explosive fashion. “My Lovin’ Is Digi” is grand and ridiculous and sublime; pairing a huge string loop with a chorus that’s sung with hilarious gravity: “Sometimes, I find someone fuckin’ with my pussy.” Then there’s “Domestic Violence.” Jesus Christ, “Domestic Violence.” An ugly, misanthropic argument between RZA and guest Jamie Sommers, the track is both a raw nerve of rage and bitterness, and a massively successful piece of entertainment. Hearing Sommers laundry list all the things about RZA that “ain’t shit,” how could you not join in?

78. Leaders of the New School – A Future Without A Past … (1991)

78. Leaders of the New School – A Future Without A Past … (1991)

The title of Leaders of the New School’s debut album is a reference to youth, and all the hope and possibilities it implies. And it completely delivers on that idea. Charlie Brown, Busta Rhymes, Dinco D and DJ Cut Monitor Milo inject every track with endearing, juvenile energy – these guys weren’t just skilled MCs, they were kids whose dreams were coming true, and their joy informed everything they laid to tape during these sessions. This is what makes A Future Without A Past one of the upper-echelon Native Tongues albums; where A Tribe Called Quest and De La Soul were exploring the power of positive thinking, Leaders of the New School was about innocence. A loose schoolyard concept informs classic tracks like “Case of the P.T.A.,” where the guys reflect on how parents and teachers just don’t get it over a completely infectious New Jack Swing groove, and “Show Me A Hero,” a “Gambler”-lifting warning shot to bullies in which Busta steals the show just by reciting his height and weight. If the rising star’s commanding baritone tends to shine just a little brighter than his bandmates, it was all part of LOTNS’ perfect pH balance, leveling out the bizarre shrieks of Brown and the steadying force of Dinko. Hearing them gleefully playing off each other really shines a light on how much the group dynamic has faded from modern hip hop. If you ever get tired of hearing solo records littered with guest spots, crank this up loud, and rejoice in the blissful synergy. Who cares if it gets you detention?

77. Lou Reed – Magic & Loss (1992)

77. Lou Reed – Magic & Loss (1992)

Lulu, Lou Reed’s 2011 collaboration with Metallica, quickly and unfairly became shorthand for an artistic train wreck. I’m happy it exists, as proof of how little Reed cared about optics. You could always count on his art being unfiltered. And maybe never more so than his 1992 effort Magic & Loss. Shaken by the death of a friend from cancer, Reed sat down and wrote lyrics that are as subtle as chemotherapy. He marvels at the fact that the same thing that killed people at Chernobyl was helping his friend buy time. He wrestles with ideas of spirituality, bowing to their sanctity one moment, deriding them as “mystic shit” the next. And through it all, no matter how crushingly depressing the songs become, Reed handles them with that classic sense of cool, his resigned sing/speak translating it all into something like hope. He’s always been great at tackling material rich in conflicting moods – “Perfect Day” kicks your ass every time, because it’s about happiness in the context of sadness. Magic & Loss is “Perfect Day” on steroids, then, an album that finds beauty and mystery in the brutal unfairness of life. “I’m sick of looking at me/I hate this painful body,” he sings over the lone, mournful guitar figure on “Magician,” a harrowing tale of a spirit longing for freedom that’s among his best work. Like the album it anchors, it’s riddled with loss, yet feels like magic.

76. Depeche Mode – Violator (1990)

76. Depeche Mode – Violator (1990)

When you’re alone, you can rule your own universe. It’s a theme that’s been used for several classic pop songs about adolescence. But when I first saw the video for Depeche Mode’s “Enjoy the Silence,” I’d never heard “In My Room” or “I Am A Rock.” I was in 7th grade, an introverted kid who typically loved extroverted music – bands like Led Zeppelin, AC/DC and Guns n’ Roses possessed such audacious confidence, it seemed like an interplanetary transmission to a boy like me. But the “Enjoy the Silence” video spoke to me on a deeper level, and could very possibly have been the first work of art to do so. It told me that I wasn’t the only one who shied away from social situations, that, in fact, it was a kingly pursuit to avoid the everyday noises of life. “Words are very unnecessary/They can only do harm,” sings David Gahan as he walks through one gorgeous landscape after another, dressed in a crown and cape and carrying a lawn chair, stopping from time to time to heed the direction of the song’s title. Violator is full of introspective struggles like this – my 12-year-old brain wasn’t savvy enough to understand these songs that wrestled with ideas of faith, and truth, and love. But those haunting goth-pop melodies were more than enough to make me obsessed; plus, as a Catholic school kid I could sense the delicious sacrilege that was being committed on “Personal Jesus.” I loved this album then, despite it standing out of my cassette collection like a sore thumb, and it has only become more poignant with age. The more I’ve discovered about why I love Violator, the more I’ve learned about the younger me, that awkward king of his own quiet world.

75. Prince Paul – A Prince Among Thieves (1999)

75. Prince Paul – A Prince Among Thieves (1999)

Given the gritty truths and intense melodramas that have been such a huge part of hip-hop – especially its 1990s golden age – it’s surprising that the genre has given us no stone-cold brilliant concept albums. Is what you’d say if Prince Paul had never made this, easily the greatest hip-hop concept album of all time, and one that I’d take over Tommy any day of the week. A Prince Among Thieves is the story of Tariq, an aspiring rapper and fast food worker who dreams of using his art to get rich and provide for his mother. When he lands a cherry meeting with Wu-Tang Clan, Tariq needs to raise some money to pay for studio time – his demo is a little rough – so he dips his toes into the drug game to make ends meet. While it’s predictable that this story would end tragically, Prince Paul infuses it with flash-forwards, Shakespearean betrayals and bursts of dark comedy, telling a tale that never gets confusing, and always keeps you on your toes. Paul’s production work is on the level with his classic De La Soul material – “Steady Slobbin'” and “What You Got” feature some of the most irresistible soul loops he’s ever dug up. The actors are totally convincing, and guest stars like Kool Keith, Chris Rock, Everlast and Big Daddy Kane make for a hell of a cast. Nobody shines brighter than the star though – Breeze Brewin’ is the main reason we sympathize so much with Tariq; he’s the perfect, unassuming hero in the skits, and his steady, tight flow is the backbone of the majority of the songs.

74. Roger Waters – Amused To Death (1992)

74. Roger Waters – Amused To Death (1992)

After releasing the final Pink Floyd album in 1983 – the underrated anti-war elegy The Final Cut – Roger Waters got into a weirdly allegorical groove, from his pervy-road-trip-as-metaphor-for-something-I-don’t-really-understand solo debut The Pros And Cons Of Hitchhiking to the guy-in-a-wheelchair-ends-capitalism follow-up, Radio K.A.O.S. Not to disparage those albums, both of which have aged far better than anything the David Gilmour-led edition of Floyd ever recorded, but everything about Amused To Death feels like Waters getting back to business, saying to hell with prog-rock librettos and writing the kind of acidic sociopolitical material that made The Wall and The Final Cut so unforgettable. “And the Germans killed Jews and the Jews killed the Arabs and the Arabs killed the hostages and that is the news,” his wonderful backup singer P.P. Arnold belts on “Perfect Sense, Part I,” and that’s the basic theme of the record – organized religion, governments and the media colluding to support humanity’s vilest sins. Because this is a solo Waters album, things do get too preachy for comfort from time to time (especially an uber-cheesy battleground play-by-play from Marv Albert). But you’ve gotta forgive him for these moments, because his rage is so pure, his hook-free arrangements so beautifully meditative, his vision so artful. He spends much of Amused to Death musing about what God wants (spoiler alert: it’s all bad stuff). Say what you want about the man upstairs, but he gave us Roger Waters, and that’s a check in the “pros” column for sure.

73. Helmet – Meantime (1992)

From the moment I first heard “Unsung,” which I’m guessing I saw on Headbanger’s Ball, Helmet’s major label debut became an album to save up my allowance and buy (quick side note – nothing will ever sound sweeter to me than the CDs I had to save for a month to be able to afford. Great music will always give me chills, but never again will I feel the blissful release of a record that lives up to my own, self-inflicted hype machine). And while the balance of Meantime didn’t possess anything quite as brutal as that amazingly simple riff, it was perfect for the kind of teen looking to project his weirdo angst on something harder and snarlier than Nirvana. Mixing the mammoth riffage and clipped shouts of Page Hamilton with drummer John Stanier’s deep-in-the-pocket breaks, Meantime was loud, nasty, groove-based hardcore, a sound that hurts just as good 20 years later. Sure, there’s plenty of pain-obsessed Trapper Keeper poetry – Hamilton’s jealous cheerleader screams of “You’re better … die!” being the lowest point. But the guitars are so punishing, and the rhythms so gut-punching, they would smother any attempt at refined lyricism like the runt of a litter.=

72. Sleater-Kinney – Dig Me Out (1997)

72. Sleater-Kinney – Dig Me Out (1997)

“Words and guitar/I got it!” What better way to sum up the joyful noise of Dig Me Out than this chorus to one of its many unshakeable standout tracks? Sleater-Kinney’s third album, and first for Kill Rock Stars, provides equal helpings of molten punk shredding and bouncy British invasion melodies – it’s not a coincidence that its cover is an homage to The Kink Kontroversy. The record sounds for all the world like a trio of gals who love nothing more than plugging in and screaming their guts out. (Which reminds me, Screaming Females’ Ugly, one of my front-runners for the best album of 2012, would in no way exist if not for Dig Me Out.) This palpable exuberance is what makes Dig Me Out something special; instead of wallowing into lines like “I wear your rings and sores/In me, it shows,” singer Corin Tucker sets fire to them, her wild, quavering pipes proving that the death of grunge didn’t stop the Seattle scene from spitting out some startlingly talented, unpredictable voices. Of course, you can’t get by purely on energy. Dig Me Out is riddled with killer pop melodies, Carrie Brownstein’s shit-hot guitar playing, and deftly layered sequences that belie the whole garage band aesthetic – take “Words and Guitar,” where Tucker’s vocal devolves into a primal scream and Brownstein chimes in with a cheery backup vocal (“Can’t take this away from me/Music is the air I breathe”), all over a sun-kissed riff straight out of a Searchers song. Sleater-Kinney makes it all sound exhilaratingly simple, as sure a sign as any that we’re hearing a great band at its peak.

71. Pearl Jam – Ten (1991)

71. Pearl Jam – Ten (1991)

When I was 14, I considered Ten to be one of the Great Rock Albums, on a level with Led Zeppelin II or Back In Black. But if you’ve read my introduction to this list, you’ll understand why I was nervous to listen to Pearl Jam’s monster debut front to back, for the first time in at least a decade – what Ten has inspired in its wake has been pretty horrifying. And I’d be lying if I said I didn’t cringe during “Once,” the album’s propulsive opening track. I can appreciate melodrama, but as Eddie Vedder growled “Once upon a time/I could love myself,” I realized how rough around the edges this gifted vocalist was in 1991. Vedder connected with listeners from the get because he sang with naked emotion, but on Ten, he often gets lost in these waves of feeling, his grunts and wails coming off almost comical. At the end of “Once,” Vedder lets loose his most heinous guttural burst (“YUH-HEA-HEA-YUH-HEA-HEA!!!!”), which I will now claim as the #1 reason Chad Kroeger, Scott Stapp and Chris Daughtry sound like they do. That’s all to explain why Ten is #71 on this list, instead of in the top 20. It remains a smorgasbord of killer guitar riffs, and is full of songs that shamelessly aim for arena nosebleeds, with none of the artsy experiments and ham-fisted politics that would make vs. and Vitalogy so uneven. And when Vedder calms down, his vocals are gorgeous – the ballads “Oceans” and “Release” are two of the album’s strongest cuts as a result. Then there’s “Alive,” perhaps the perfect example of how Pearl Jam combined the angst-ridden energy of grunge with the comfortable, crowd-pleasing tropes of classic rock – if you thought existentialist crises and guitar solos couldn’t mix, here’s your proof.

70. Beck – Midnite Vultures (1999)

70. Beck – Midnite Vultures (1999)

“Loud/quiet/loud” is about as standard as rock n’ roll formulas get. But few artists have applied the concept to entire albums the way Beck did from the mid-’90s to the early ’00s. After his sample-heavy, Def Jam-meets-Folkways pastiche Odelay made him an alt-rock hero in ’96, he followed it up with a gorgeous, late afternoon stroll of a country album. Which meant that he was due for a “loud” album by the time Midnite Vultures came around. And holy shit, did he deliver. Not only is the album in-your-face in a sonic way – being pretty much a string of intense electro-funk workouts from beginning to end – but its overall aesthetic is as thrillingly brash as the neon-green cover art. Beck’s trademark non sequiturs remain in full force, but they’re applied in a more distinctly sexual milieu, with titles like “Peaches & Cream” and “Milk & Honey,” and pick-up lines that reference satin sheets, tropical oils, Hyundais and JC Penney. It’s like a parody of a Prince album that just happens to be as musically adventurous as it is hilarious, a snapshot of an artist dealing with supersized expectations by making the craziest party album he possibly could. The music is wildly imaginative throughout, from the slick game show horns of “Sexx Laws” to the fembot synth pop of “Get Real Paid” and the classic Stax groove of “Debra.” With full-on falsetto verses, whispery sex talk and Vegas-ready horn stabs, “Debra” is an ingeniously absurd epic, and one of the most purely enjoyable R&B cuts of the decade. It’s that mix of rare quality and endearing irreverence that still makes Midnite Vultures a thrill of a listen. Of course, Beck’s next release was a tear-streaked breakup album.

69. Wu-Tang Clan – Wu-Tang Forever (1997)

69. Wu-Tang Clan – Wu-Tang Forever (1997)

If a decision to make a double album ever felt like a no-brainer, it was this one. After Wu-Tang Clan blew the doors off of hip-hop with the indefatigable Enter the Wu-Tang: 36 Chambers, ensuing solo albums from GZA, Ghostface Killah, Ol’ Dirty Bastard and Method Man all became classics in their own right. So if Wu-Tang Forever was going to give all of these evolving mythologies and expanding egos any kind of breathing room, it was going to take two discs. RZA makes the most of the extended running time, his approach more cinematic than ever before, wrapping those trademark kung-fu sound bites and blaxploitation soul loops in ominous layers of strings. Which was all too appropriate, because if anything, the crew’s successes had made their worldview darker. This was the second album from the biggest rap crew on the planet, and they rarely, if ever, brag about money on it – something that would probably never happen in our post-Puffy and -Kanye world. The first single, “Triumph,” was a killer bee swarm of a showcase track; from the molten-hot rhymes of Inspectah Deck’s first verse on, the mood is more confrontational than triumphant. Because at its peak, the Wu wasn’t interested in non-fiction boasts. It was about world-building. They knew that if Wu-Tang Forever could do what most movie sequels can’t – stay true to the characters while taking them in compelling new directions – the money would come. And as all of the Wu Wear in my closet circa 1997 could attest, they most definitely pulled it off.

68. Nirvana – In Utero (1994)

68. Nirvana – In Utero (1994)

If what happened hadn’t happened, and In Utero didn’t end up being Nirvana’s de facto swan song, it wouldn’t be taken so gosh darn seriously. Which would be infinitely to its benefit. Because while the record does work as Kurt Cobain’s ragged middle finger to the trappings of rock stardom (his lyrics had never been so beautifully barbed), it works even better as a snapshot of geniuses fucking around. Beyond the accomplished demon-wrestling you get from the singles, In Utero is littered with blasts of punk deconstruction that are the sonic equivalent of a movie scene where an actor gets to destroy something. As Cobain screams maniacally during “Tourette’s” or bends his squealing guitar skyward on the riff to “Scentless Apprentice,” it sure sounds like he was having fun. Then there’s the irrefutable evidence. Toward the end of my favorite of these anarchic cuts, “Milk It,” Cobain laughs as he delivers the thoroughly batshit chorus for the last time – “DOLL STEAK! TEST MEAT!” In that moment, any angst you were feeling goes up in smoke.

67. Beastie Boys – Ill Communication (1994)

67. Beastie Boys – Ill Communication (1994)

With the release of Ill Communication, its third-straight stone-cold masterpiece, the Beastie Boys had completed one of the most remarkable artistic evolutions in pop music history. Within an eight-year period, the trio had gone from a snotty frat boy marketing concept to one of popular music’s most sonically expansive and socially conscious acts. If Licensed To Ill purists had any hopes that this one would hearken back to that fun-in-spite-of-itself debut, they were dashed on the opening cut, “Sure Shot.” Over that hallowed jazz flute sample, MCA poured out his regret over the Beasties’ once-misogynistic bent: “I want to say a little something that’s long overdue/The disrespect to women has got to be through/To all the mothers and the sisters and the wives and friends/I offer my love and respect to the end.” Blending this kind of soul-searching with infectious rap free-for-alls, blistering punk romps and Mayfield-caliber funk instrumentals, Ill Communication is the sound of hip-hop ending its adolescence, flexing its muscles and realizing its own power.

66. Air – Moon Safari (1998)

66. Air – Moon Safari (1998)

If you wanted to look cool smoking a cigarette in the late-’90s, putting Moon Safari on repeat was a pretty safe bet. Taking all of the stereotypical American ideas of what constitutes “French music” – loungey jazz, whisper-soft female vocalists, songs with “sexy” in the title – and filtering them through electronica’s spaciest kaleidoscope, Air’s debut album was a beautiful, warm bath of an acid trip. This was music that people in the ’90s would put on “chill-out” mixtapes to show they were men of many moods, deeper than the stammering, opinionated goofball on the surface. Not that I ever did that or anything. But Moon Safari is so much more than “chill-out” music – it’s not so much dreamy as it is an actual dream, a hazy sonic adventure that makes good on the promise of its title, where elegant bass lines guide you through alien, synthetic landscapes, with the occasional full-blown pop song to remind you that you’re earthbound. Air went on to make even more adventurous music, much of it lovely, none of it a voyage like this one.

65. Alice In Chains – Dirt (1992)

65. Alice In Chains – Dirt (1992)

I’m trying to figure out how to say something different from my take on Pearl Jam’s Ten earlier on this list, but the experience of listening to Dirt for the first time in a decade was similar. But before I crap on your memories, let’s be clear – this is a great metal album, steeped in a malaise that came from a frighteningly real place. It provides moments of clarity that feel like blasts of pain poking through the anesthetic. Alas, not being a teenager anymore means Dirt is not an album I will reach for often. What can I say, I like my bleakness with a chaser of hope these days. Plus, like vintage Eddie Vedder, Layne Staley isn’t as infallible as I once thought. He can truly haunt a song, a la Ozzy Osbourne in his prime. But also like Osbourne, it’s the only setting he’s got. The moments where Staley’s tortured crooning inhabits Jerry Cantrell’s demonically beautiful guitar riffs – e.g. “Them Bones” and “Would?” – are what made Alice In Chains special, and there are enough of them here to make Dirt a classic.

64. Matthew Sweet – Girlfriend (1991)

64. Matthew Sweet – Girlfriend (1991)

To people who grew up on The Beatles, ELO and Cheap Trick, and then had to endure mainstream rock radio throughout the ’80s, Matthew Sweet’s Girlfriend must have felt like a warm hug from mom. Pairing feelings of elation and vulnerability with shimmering power pop riffage and stacked-high vocal harmonies, Sweet’s third album has a timeless quality to it (the song title “Winona” is the only clue that this is from the ’90s). The songs explore the creation and destruction of relationships in universal terms – love makes self-deprecating feelings vanish; somebody falls for a preacher’s daughter; a guy who thought he knew his girl realizes he was wrong. Without getting specific, Sweet turns phrases like knives – “You can’t see how I matter in this world,” he pleads amongst the beautiful wreckage of “You Don’t Love Me.” His kinda nerdy, straightforward tenor makes all of the sentiments feel genuine, those hooks still as fresh and addictive as a long gaze into the eyes of the one you love.

63. Randy Newman – Bad Love (1999)

63. Randy Newman – Bad Love (1999)

After 1988’s Land of Dreams, Randy Newman took a long break from traditional record-making to focus on film music (and his so-so Faust musical). I’d bet the 11 years between Dreams and Bad Love made for the most lucrative period of his career. You might’ve thought that all those Oscar nominations and Pixar paydays would soften the guy, that when he got around to recording another batch of songs, they’d be somewhat pleasant – even, dare I say, optimistic. But Bad Love isn’t just a work of caustic satire typical of Newman’s oeuvre. It’s the bitterest, saddest, most unflinchingly personal work of his career. The songs depict families falling apart in front of televisions, dirty old men cursing at women half their age, native peoples suffering and dying. Which would make for untenable listening if most of this stuff wasn’t also hilarious – especially “The World Isn’t Fair,” an open letter to Karl Marx that finds Newman acknowledging his good fortune by talking about how preposterously undeserving of it he is. Like most self-absorbed people, Randy’s incapable of change here, and we’re all the richer for it.

62. Mercury Rev – Deserter’s Songs (1998)

62. Mercury Rev – Deserter’s Songs (1998)

It’s impossible for me to listen to Deserter’s Songs without constantly comparing it to a record that came out a year later – The Soft Bulletin. Mercury Rev’s fourth record shared the same producer as that Flaming Lips masterwork, the brilliant and clearly influential Dave Fridmann. So it’s no coincidence that both records possess the same ambitious, slightly disorienting template, mixing lush, Nelson Riddle arrangements with quirky, contemplative musings, like a band used backing tracks for a Great American Songbook tribute to write songs about spider bites, or moles with telephones for eyes. But while they might be the same type of animal, these records are also different breeds – Deserter’s being one that prowls across much darker emotional territory. As singer Jonathan Donahue spins yarns about nightmares and doomed relationships with an unvarnished Neil Young yodel, Fridmann piles on the woodwinds, strings and saw solos like an old-time Disney composer. It’s a birthday cake with a scotch egg in the center, a walk to the gallows that runs through Martha’s Vineyard, an album with a title drenched in self-imposed loneliness that makes good on it in the most unexpectedly stunning way.

61. Smashing Pumpkins – Gish (1991)

61. Smashing Pumpkins – Gish (1991)

Gish is one of the most compelling debuts in rock history, and not just because it gives us an unfiltered look at what made Smashing Pumpkins one of the greatest arena-rock bands of the 1990s. It’s that in those very same qualities laid the seeds of the group’s demise. While by far the rawest recording that Billy Corgan has deemed acceptable for our ears, Gish is still marked by a proudly meticulous approach to rock record-making, its guitars layered richly to create walls of sound that envelop you with warmth, even while they strain your speakers to the limit. Of course, once Corgan got on the short list of successors to the Cobain throne and became obsessed with his own brand of stylized melancholy, the speaker straining stayed, and the warmth didn’t. And that just makes songs like “Window Paine” even more of a pleasure to experience in 2013 – a jaw-dropping ballad that features some of the most gorgeously punishing guitar playing of the ’90s. Hopelessly yearning for Corgan to make another record like this someday? That’s a worthwhile kind of melancholy.

60. Red Hot Chili Peppers – Blood Sugar Sex Magik (1991)

60. Red Hot Chili Peppers – Blood Sugar Sex Magik (1991)

Of all the mega-selling, on-the-charts-for-years rock albums, have any been as weirdly schizophrenic as Blood Sugar SexMagik? After scoring a minor hit in 1989 with a rather grating cover of Stevie Wonder’s “Higher Ground,” Red Hot Chili Peppers used its next album to shamelessly court the mainstream. And spit in its face. And forget all about it because it had a boner. And then court it again. BSSM is on this list because it remains the band’s most fully realized work, a 17-track tapestry of immaculately crafted funk and richly realized, anthemic rock. When John Frusciante’s elegant guitar chatter intertwines with Flea’s lyrical bass lines on tracks like “If You Have To Ask,” “Mellowship Slinky” and “Apache Rose Peacock,” they prove that party music for buttheads can be as artful as anything else. But as always, the band’s X factor is singer Anthony Kiedis, whose political rants and sexual fantasies have always been as developed as your average 13-year-old (“Sir Psycho Sexy” is BSSM’s most ambitious song, and thanks to Kiedis and his vagina thesaurus, it’s also its most embarrassing). Yet, on this record, Kiedis also convincingly hates the honesty in his face, sees the world through the eyes of an addict, and gets endearingly goofy while covering Robert Johnson. This album is where the bravado of the penis-sock days met the polished, dad-friendly balladry that’s defined Red Hot Chili Peppers ever since. Why is that a good thing? If you have to ask, you’ll never know.

59. Digable Planets – Blowout Comb (1994)

59. Digable Planets – Blowout Comb (1994)

To the delight of aspiring poets, kids who couldn’t get into bars, and white people with dreadlocks, coffee shops were all the rage in the 1990s. I can remember spending way too much time at a place in Buffalo called Stimulance, pretending to like cappuccino while sitting on ironically garbage-picked furniture. In retrospect, this fad had a few positive aftereffects – like the snob-worthy java you can find around every corner these days, and the all-too-brief popularity of groups like Digable Planets. Fusing the cadence of live poetry with the jazzy sensibilities of Native Tongues hip-hop, this Brooklyn trio scored a hit with 1993’s “Rebirth of Slick,” and used all of its resultant goodwill to make this sprawling, career-murdering, aggressively chilled-out masterwork. Eschewing samples in favor of live musicians, Blowout Comb makes the jazz-rap experiments of its peers sound like novelty tracks. Saxophones trill; vibraphones echo; live drums burrow deep in the pocket, and emcees Butterfly, Ladybug and Doodlebug deliver verses with soft, rhythmic power. Their voices are such a part of the aesthetic that you barely remember what you just heard, drifting happily from track to track. To listen to Blowout Comb is to experience new vistas of dreamy funk, which lull you into closing your eyes, as the summer sun glows behind them.

58. Basement Jaxx – Remedy (1999)

58. Basement Jaxx – Remedy (1999)

I was a loyal subscriber to Rolling Stone and Spin for most of the ’90s, and have a vague recollection of being told in no uncertain terms that electronica was going to be the next grunge. I certainly bought into that hype – spending $17 on Tricky’s Maxinquaye and trying very hard to like it, for example (I still don’t get it) – but it wasn’t until I was in college and heard Basement Jaxx that I thought those writers might not have been totally full of shit. Electronica never took off, I know, but maybe if something as funky, melodic, and unabashedly hook-filled as Remedy had hit five years earlier, we’d be left with more than mental images of that Prodigy guy’s seizure-dancing. Or maybe I’m just not a big electronic music guy (Daft Punk’s never really done it for me either), and Remedy is one of those records that only requires a pulse to enjoy. Either way, the thing is as fun to crank as ever, a dance record that uses digital elements as efficiently as a great punk band uses chords.

57. Ben Folds Five – Ben Folds Five (1995)

57. Ben Folds Five – Ben Folds Five (1995)

Nerdy dudes can be like fine wine – once they reach a certain age, they turn to vinegar. Take Ben Folds, who was the driving creative force behind this album, an electrifying slab of sensitive guy rock and roll that purposely excluded guitar solos on one outcast anthem after another. “You can laugh all you want to/But I’ve got my philosophy,” he crooned, with a reactive confidence that sounded earned. With “Underground,” he delivered a spot-on, sardonic takedown of music scene snobbery that was simultaneously one of the most infectious pop songs of its time. And “Boxing,” a gorgeous waltz in the form of a tear-stained, existentialist letter from Muhammad Ali to Howard Cosell, remains a stunningly imaginative piece of songwriting. Ben Folds Five followed this with greater commercial success, including some lovely work here and there. But the formula was eroding even then – the band’s biggest hit was about how abortion is tough on men, and that was followed up by a single with the chorus, “Give me my money back, you bitch.” Folds’ talent is undeniable, but only on Ben Folds Five was it bottled correctly.

56. Soundgarden – Badmotorfinger (1991)

56. Soundgarden – Badmotorfinger (1991)

Just like Metallica’s first crossover metal album was And Justice For All …, Soundgarden’s courting of the mainstream began here. And just like AJFA was superior in every way to its blockbuster follow-up, Badmotorfinger has held up over the years in a way that makes 1994’s massive hit Superunknown look like a pop culture relic. Now, I like Superunknown a lot. It’s #96 on this list because it did a fine job bridging the artful brutality of its previous work with pleasant-enough grist for the MTV heavy rotation mill. But Badmotorfinger is the greater accomplishment, because while it punishes your ears more than anything this side of Slayer, its melodies and ideas are so compelling, they invite you in. Religious iconography rubs shoulders with prisoners about to burst with rage. Kim Thayil’s riffs are as dark and sludgy as pure crude; Chris Cornell’s throaty, banished angel screams are somehow both operatic and thrillingly raw. It’s serious metal music made for all of us to enjoy, and it’s galaxies away from “Black Hole Sun.”

55. Neil Young – Harvest Moon (1992)

55. Neil Young – Harvest Moon (1992)

In the ’90s, we started to get a good idea of how the legendary artists of the ’60s and ’70s were going to deal with aging. Paul McCartney would dye his hair and keep on writing love songs. Stevie Wonder would pretty much retire. Bob Dylan would shroud himself in mortality and end up resuscitating his muse. But no artist stepped into middle age as organically as Neil Young did on Harvest Moon – an album of gentle country songs about life passing by, made to be listened to on a big front porch in the twilight. The then 47-year-old certainly doesn’t ignore the darkness, singing about the aching desperation of divorce, a waitress haunted by regrets, and a man contemplating suicide in a minivan. But his gently quavering voice, sympathetic turns of phrase, and clear-eyed belief in true love (especially on the title track) tip the scales from depressing to life-affirming. Then there’s “Old King,” a jaunty bluegrass eulogy to a hound dog that’s about as much fun as anybody could have contemplating death. If you could prescribe treatment for the human condition, Harvest Moon would be FDA-approved.

54. Eels – Electro-Shock Blues (1998)

54. Eels – Electro-Shock Blues (1998)

Moving on, from one ruminative, regret-laden work to what is arguably the Grand Poobah of ruminative, regret-laden 1990s albums. After losing both his mother and sister in a short period of time, Mark Oliver Everett – the one-man phenomenon behind Eels – made a record that wallows in raw cynicism and deep, lying-on-the-bathroom-floor sadness (at its lowest, quietest moments, you can almost smell the porcelain). Lyrically, Elecro-Shock Blues is an open vein (e.g. “My life is shit and piss”), and it would be light years from this list if those often-brutal sentiments weren’t balanced out by the production, which was eclectic enough to make a fan out of Tom Waits. Among the many gorgeous acoustic ballads, there’s the lurching rhythms and crackling found sounds of “Cancer for the Cure,” the dance-folk breaks of “Last Stop: This Town” and the sexy Morphine rumble of “Hospital Food.” Hence, by the time Everett rewards us on the closing “P.S. You Rock My World” by admitting to a new appreciation for being alive, we’re wishing the whole beautiful thing wouldn’t end.

53. The Flaming Lips – In A Priest-Driven Ambulance (1990)

53. The Flaming Lips – In A Priest-Driven Ambulance (1990)

Unlike most of the epic rock music released in the ’90s, The Flaming Lips’ magnum opus – 1999’s The Soft Bulletin – was a gorgeously un-ironic embrace of hope and belief. But it was also the natural endgame of a creative impulse that was first exhibited nine years earlier, on the band’s fourth album. In A Priest-Driven Ambulance finds Lips songwriter Wayne Coyne deep in a Christ obsession, his analytical and spiritual sides clashing, adding an exotic tension to the ragged helium of his voice. “While I’m still myself/Your blankets covered me,” Coyne sings on the triumphant psych-folk opening “Shine On Sweet Jesus,” swooning at the beauty of belief. But over the spare chords and insistent crickets of “There You Are,” there’s the sickening chill of doubt – “It makes you think that God was fucked up when he made this town.” By decade’s end, The Flaming Lips stood firmly on the side of belief in something more. Without stunning metaphysical wrestling matches like this album, that level of peace wouldn’t have been achievable.

52. Soul Coughing – Ruby Vroom (1994)

52. Soul Coughing – Ruby Vroom (1994)

Like countless white suburban teenagers in the 1990s, I was magnetically drawn to albums like The Chronic and Enter the 36 Chambers – raw, confident, impeccably produced works of art that possessed an egomaniacal energy I could leech off of. But I was just as crazy about bands like Barenaked Ladies and Primus, whose strident dorkiness spoke to the chicken-armed X-Files fanboy in me. So when I first heard Ruby Vroom’s opening song, “Is Chicago, Is Not Chicago,” it was like hearing those two factions of my CD collection – and those two idealized versions of myself – gelling, and it kicked more ass than it had any right to. Few bass lines have ever burrowed as deep in the pocket as Sebastian Steinberg’s does here – the groove produced by Steinberg and drummer Yuval Dabay transcends the standard definition of rhythm, inciting a primal, emotional reaction that would make Elaine Benes feel like Gregory Hines. And when M. Doughty tells you that “Saskatoon is in the room” in his flat, nasal voice, you realize that post-ironic nerdy nonsense can play in the same sandbox as supreme-sonic-super-badness. That the silly shit you think is funny might not be the polar opposite of funky. That it’s not entirely impossible to dream that you could, one day, bring the motherfuckin’ ruckus.

51. Bjork – Homogenic (1997)

51. Bjork – Homogenic (1997)

Electronic music is fertile ground as a metaphor for sadness. Whether it’s Kanye West undergoing therapy-by-AutoTune on 808s & Heartbreak, David Bowie nailing what a “sense of doubt” sounds like during his Berlin period, or Portishead’s entire catalog, synthesized notes do a bang-up job representing a lack of emotional warmth. Which makes Bjork’s Homogenic a special album beyond the immediate bounty of its lush, philharmonic-tronica production. After the breathtaking genre whirlwinds of Debut and Post, Homogenic finds the artist working in one sonic cul-de-sac for the first time. The production makes you think twice about the originality of 21st century Radiohead – ghostly drum loops and synth patches give way to stunning string arrangements. It’s dizzyingly dour music that would make the perfect accompaniment to songs about winter, or war, or whatever kind of “sour time” you want to moan on about. But instead, Bjork uses them to sing about love as a connection that transcends the physical, that’s as inevitable as the tide, that surrounds us all whether we know it or not. Even when her music’s at its tamest, her impulses are anything but.

50. Ol’ Dirty Bastard – Return To The 36 Chambers: The Dirty Version (1995)

50. Ol’ Dirty Bastard – Return To The 36 Chambers: The Dirty Version (1995)

Even though there were nine talented rappers vying for our attention on Wu-Tang Clan’s debut album, it was clear that Method Man was the one being pegged for a solo career. But while Mr. Meth did deliver that first Wu solo record, it was Ol’ Dirty Bastard who delivered the first Wu solo masterpiece. In hindsight, this was far from a sure thing. Because while every ODB verse on Enter the Wu-Tang is a gem, part of his impact came from the way he recklessly exploded onto tracks, spilling jet fuel in his wake. Not exactly the formula for anchoring a 15-song album. Except Return to the 36 Chambers: The Dirty Version wasn’t concerned with formula. It begins with an extended free form spoken word track in which ODB introduces himself, cries about getting gonorrhea, then sings an Andrew Dice Clay-esque spoof of “The First Time Ever I Saw Your Face” in a quavering, deep-throated croon. The record lets us spend an extended amount of time with the artist, and it reveals a man obsessed with STDs, the Great American Songbook, and a raw, off-the-cuff rhyming style that electrifies everything it touches. Almost 20 years later, it’s clearer than ever that this is no cheap laugh for hip-hop rubberneckers. This is genius, unfiltered.

49. Toad The Wet Sprocket – Dulcinea (1994)

49. Toad The Wet Sprocket – Dulcinea (1994)

A band remembered mostly for its crappy name and a pair of wide-eyed jangle-pop love songs, Toad the Wet Sprocket’s only value in 2014 should be to the producers of I Love the ’90s: Everything Else We Haven’t Talked About Yet. Except for the fact that Dulcinea, the Santa Barbara group’s fourth album, is a lush, tender, literally quixotic triumph. Released three years after the band’s commercial breakthrough, fear, the record smartly refines the swooning, alt-rock hamminess of hits like “Walk On the Ocean,” adding delicate strains of folk and country that make the morose, clean riffage feel authentic. It was the perfect accompaniment to the spiritual bent of singer/songwriter Glen Phillips, ensuring that tracks like “Fly From Heaven” and “Reincarnation Song” remain humble in their inquiries. The result is a record with a much longer shelf life than fear, with songs that put us all in the shoes of Don Quixote, elegantly losing our minds with hopes of true love and a higher standard for humanity.

48. Portishead – Portishead (1997)

48. Portishead – Portishead (1997)

“Nobody loves me/It’s true,” mourned Beth Gibbons on Dummy, Portishead’s essential, trip-hop hall of fame debut. Three years later, the Bristol quartet’s perspective was a bit more refined, yet no less intoxicatingly dark. “All Mine,” the first single, practically has you thinking it’s an old-fashioned love song, with Gibbons singing, “When you smile/Ohhh how I feel so good” over horns that stab and accuse like a Bernard Herrmann Bond theme. The reverie doesn’t last, of course, with the vocalist taking her haunting, Nico-via-Kate Bush pipes into the upper registers to make a chilling prediction – “Make no mistake/You shan’t escape.” If the first Portishead record was about misery, this one was about Misery. Gibbons’ incredibly effective tone once again finds its soul mate in producer/bandleader Geoff Barrow, who unleashes a gorgeous array of crackling, unsettling samples, somber keyboards, echoing drums and inspired scratching. It was a gift to lovers of torch singing, DJ Premier and all forms of gothic art, one generous enough to satiate listeners until the band’s next effort – 11 years later.

47. Fishbone – Give A Monkey A Brain and He’ll Swear He’s the Center of the Universe (1993)

47. Fishbone – Give A Monkey A Brain and He’ll Swear He’s the Center of the Universe (1993)

As a 15-year-old person in 1993 who loved AC/DC and Arnold Schwarzenegger in equal measure, it was a foregone conclusion that I would not only see Last Action Hero on its opening weekend, but also buy its soundtrack, which featured not only my favorite Aussies but other bands I loved like Queensryche (!) and Tesla (!!!). And lo, I loved both the film and its music. But I’ll never forget the moment track 10 of the soundtrack came on. It was a metal song, and thereby should technically have been in my comfort zone. But this was a practically riff-less, crazed dirge of a metal song, a song designed not to inspire head banging, a song that whispers to you to lie down so you can become mired in its ooze. The song was “Swim” by Fishbone, which was also the first track on this, its mindblowingly diverse and preposterously entertaining fourth album. Give A Monkey A Brain … may have been the first recorded work that taught me genre rules were imaginary. There was plenty of stunning, melodic metal, alongside the frenetic ska of “Unyielding Conditioning,” the primo Funkadelic-esque freak outs “Properties of Propaganda” and “Nutt Megalomaniac,” and a pair of avant garde punk breakdowns from singer Angelo Moore. Both “The Warmth of Your Breath” and “Drunk Skitzo” made me laugh after I picked my jaw up from the floor; today their energy remains totally addictive, but they read less like comedy, and more like profound expulsions of feeling. To say the least, the rest of the Last Action Hero soundtrack has not held up half as well.

46. Uncle Tupelo – March 16-20, 1992 (1992)

46. Uncle Tupelo – March 16-20, 1992 (1992)

If I was writing about Uncle Tupelo five years ago, I probably would have railed against contemporary country music in that ignorant way that people sound when they criticize something they’ve never given a fair shake. But a gig reviewing concerts for my local newspaper put me face to face with supreme talents like Miranda Lambert, Brad Paisley and Eric Church, and I discovered that there’s plenty of incredible songwriting and irresistibly breezy melodies in today’s country-pop. Still, I prefer the approach of bands like Uncle Tupelo and their eventual spawn, Wilco and Son Volt. And I think I know why – they sound like blue-collar guys singing blue-collar songs, whereas today’s average country single sounds like a pop singer delivering lyrics that were vetted for the blue-collar marketplace. (It’s why I can admit that a universal party song like “Red Solo Cup” is a masterpiece, while pretty much anything with “truck” in the title makes my skin crawl. There’s a disconnect.) Or maybe this album is just so good that it’s skewing the larger argument in my mind. March 16-20, 1992 was the purest ode to blue-collar American life laid to tape in the 1990s. From its bare-bones title to its embrace of musty standards like “Coalminers” and “I Wish My Baby Was Born,” this is Americana in the raw. It was recorded and produced in Athens, GA, by R.E.M. guitarist Peter Buck, but his smartest move was to pretty much stay out of the way, letting the songs feel captured, Alan Lomax-style. It’s the most in synch that Jeff Tweedy and Jay Farrar ever sounded, so much so that the record’s best, most emotional track is one where they just play together, the bucolic instrumental “Sandusky.”

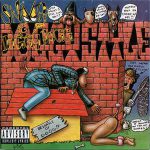

45. Snoop Doggy Dogg – Doggystyle (1993)

The first rapper we hear on this, the definitive statement from the California G-funk era, isn’t Snoop Doggy Dogg. Or Dr. Dre. It’s the forever slept-on Death Row mercenary The Lady of Rage, whose joyful, electrifying verse sets the tone for record to come – “Kickin’ up dirt and I don’t give a god damn,” she spits. It’s an immediate sign that Doggystyle is going to be more fun than Dre’s iconic 1992 opus The Chronic. While that record was concerned with settling scores and establishing myths, Snoop’s is concerned with partying and making dick jokes. His laconic flow and youthful effervescence is the ultimate counterpoint to Dre’s bloodshot Funkadelic grooves. The opening salvo of “G Funk,” “Gin & Juice” and “Tha Shiznit” is a cresting wave of positive vibes that still makes me feel like I’m blissfully plastered, with the warm sun on my face. This is the record that should’ve been named after weed.

44. Pearl Jam – No Code (1996)

44. Pearl Jam – No Code (1996)

Even when Pearl Jam was conquering the world with sweeping arena rock anthems, they actively rejected the “arena rock band” label. They stopped making videos, fought Ticketmaster, defaced #1 albums with drunken accordions and bizarre sound collages. But it wasn’t until No Code that they actually stopped sounding like rock stars. It remains the band’s most patient and honest effort, with themes of spirituality taken to heart. What hits you at first is the eclecticism – Eastern melodies and spoken word and muddy punk all rubbing shoulders. But what’s endured are the ballads, some of the loveliest in ’90s rock. There’s no attempt to mask the weariness in Eddie Vedder’s vocals or Brendan O’Brien’s loose, shaggy production. Whether it’s the somber self-criticism of “Off He Goes” or the gentle country lullaby “Around the Bend,” we’re hearing musicians so exhausted by stardom, all they had left to do was be themselves.

43. Public Enemy – Fear of a Black Planet (1990)

43. Public Enemy – Fear of a Black Planet (1990)

I can think of no better example of sampling as an art form than Public Enemy’s third album. Of all the classics made during rap’s Wild West sampling era – before attorneys got wise to the fact that producers in this new genre were chopping up copyrighted material – Fear of a Black Planet has the most consistent, fully realized vision. PE’s production crew The Bomb Squad deploys 129 samples over the course of 20 tracks, leaning heavily on James Brown and Sly Stone breaks but also mining Prince, Uriah Heep, Sgt. Pepper’s, Hall & Oates, and Vincent Price’s laughter from “Thriller.” Amazingly, the album doesn’t sound like a collage or mash-up, because The Bomb Squad treats these samples like building blocks, just 129 of the instruments used to flesh out PE’s relentless, confrontational funk. This isn’t a wall of sound. It’s a skyscraper. And when the man rapping over it is Chuck D in his prime, his voice booming like timpani, full of righteous outrage and Afrocentric pride? You can’t imagine anything ever sounding bigger.

42. Nick Cave and The Bad Seeds – Let Love In (1994)

42. Nick Cave and The Bad Seeds – Let Love In (1994)