When I moved to Stephen King’s home state of Maine this summer, I thought it would be fun (if a bit cliché) to finally read his books in earnest, and discover how I really feel about his work. For this installment, I decided to “cowboy up” – which is a thing you can do, apparently – and take on Book One of the Dark Tower series – The Gunslinger.

“Everything in the universe denies nothing; to suggest an ending is the one absurdity.”

–The Man in Black

If one wanted to take a swipe at Stephen King, the length of his novels seems to be the obvious place to start. None of the books I’ve tackled here so far have been especially bloated, but his loyal readers are certainly no stranger to shelf-punishing hardcovers. Of course, this invites accusations of King having a problem with endings, or a puffed up idea of his own literary significance, or a celebrity that handcuffs his editors. But I’m pretty sure this line of criticism is a lazy one, because I just read The Gunslinger – the first entry in King’s seven-part-and-counting Dark Tower series, and the opposite of a 1,000 page door-stopper – and it left me wanting so much more.

When this book came out in 1982, it must have thrown King junkies for a bit of a loop. Written in simple, muscular language, The Gunslinger is a starkly different genre exercise then the supernatural/domestic clash fiction that made the author famous. King borrows from an eclectic array of fantasy tropes to build his world – including spaghetti westerns, 1950s post-apocalyptic sci-fi, Arthurian legend and the multiverse theory – boiling them down to the most basic of quest stories, where the obviously good guy (The Gunslinger) follows the obviously bad guy (The Man in Black), across a desert hellscape, getting closer and closer until he finally catches up with him. Plus, there’s a kid. It’s not a bad idea on paper – King writes the weirdo Sergio Leone script of his dreams, adding his own shadows to the good and the bad, but focusing most of all on the ugly, resulting in a Cormac McCarthy-meets-J.R.R. Tolkien mindfuck of a masterpiece. That’s what I wish this book was.

What it actually is, is way too slight. So few characters having even fewer conversations, with the emptiness of the landscape getting more play than anything else. I get that when your main character is the strong, silent, Eastwood type, your story isn’t going to be dialogue driven. But there isn’t much plot here to speak of either – Good Guy follows Bad Guy from Point A (desert) to Point B (mountains). Good Guy picks up Mysterious Boy. Good Guy bonds with Mysterious Boy. Good Guy makes Difficult Choice in regards to Mysterious Boy while following Bad Guy from Point B (mountains) to Point C (fire pit on other side of mountains). The End.

Now, I’m fully aware that context is playing a role here. I read The Gunslinger immediately after finishing The Shining, a gluttonous feast of character development that puts us inside the head of a gifted child, who becomes a portal into the heads of everybody else – while also carefully laying out the dark and complicated pasts of both a haunted hotel and the family trapped inside of it. I also read The Gunslinger with the knowledge that it’s the first book in a beloved fantasy saga – something I usually have a weakness for. So you could say I went in expecting The Fellowship of the Ring, and I got a few chapters of a shorter, picture-book version of The Hobbit.

While there are elements of the story that intrigue me and will compel me to read on – most especially the beautifully regaled flashbacks that make up The Gunslinger’s pre-apocalyptic, pseudo-Arthurian origin story – King’s world just isn’t in the same galaxy as a Middle Earth. Or even a Westeros, for all its obsessive-compulsive flaws. Maybe in future installments, King will abandon the cowboy novelist pose and just write his ass off while losing himself down all kinds of bizarre rabbit holes, fleshing out the scraps of promising meat from this skeletal beginning. Maybe there will be hundreds of pages of stuff that makes the story much longer than it probably needs to be. I can only hope.

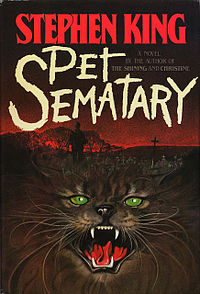

Catching Up With King #1: Pet Sematary

Catching Up With King #2: The Shining

Even though I’m merely two volumes into this little project of mine, I feel like I have a pretty solid grasp on what makes Stephen King’s best work tick. He doesn’t restrict his creepy crawlies to the supernatural realm, and that’s why his stories have struck such a resounding chord with a wide swath of humanity. Just like

Even though I’m merely two volumes into this little project of mine, I feel like I have a pretty solid grasp on what makes Stephen King’s best work tick. He doesn’t restrict his creepy crawlies to the supernatural realm, and that’s why his stories have struck such a resounding chord with a wide swath of humanity. Just like